How China’s Last Empress Lost Everything and Died in Prison an Opium Addict

Her husband grew old among his family, but Wanrong was not so lucky

(Author’s note: an earlier version of this story was published on Medium in 2021)

When I first saw Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Last Emperor, I was fascinated by its artistry and the realization that the story was new to me. Not in all my years of schooling did I learn anything about what happened to China’s Imperial family after the formation of the Republic of China in 1912 and/or after the Commun took over in 1949.

The schools I attended focused on American and European history. We kids could find China on a map (How could you miss it?), but that was about it. The story might also be new to many other people, particularly the part about the life and death of China’s last empress Wanrong.

A privileged upbringing

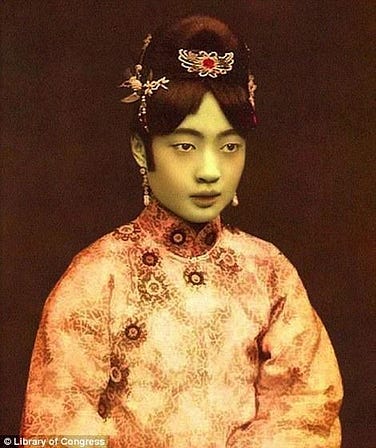

The last woman to hold the title Empress of China was born Gobulo Wanrong (郭布羅·婉容) on November 13, 1906, in Beijing, China. Gobulo was her clan name.

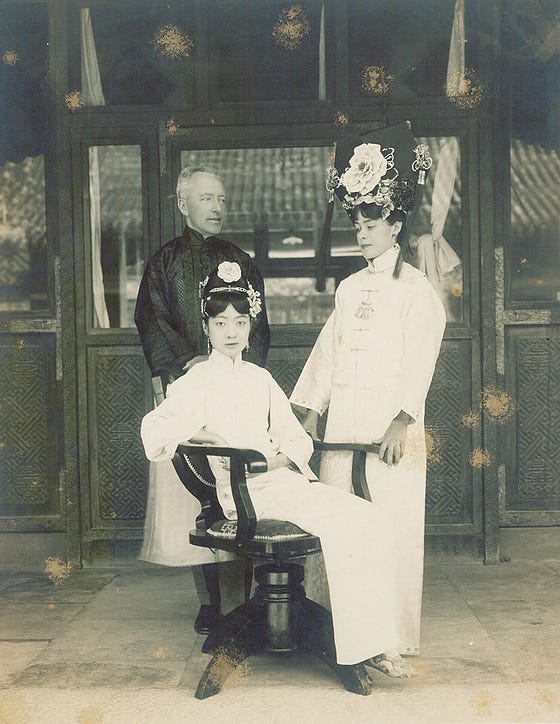

Her parents were Qing imperial court Minister of Domestic Affairs Rongyuan (榮源), and Aisin-Gioro Hengxin (恒馨)who died of childbed fever just after Wanrong was born. Wanrong was raised by her stepmother Aisin-Gioro Hengxiang (恒香), a distant relative of her mother’s. (NOTE: Because of the similarity of their names, you will often see photos from the 1920s of Wanrong’s stepmother mislabeled as being of Aisin-Gioro Hengxin, who died in 1906.)

Although she never knew her birth mother, Wanrong had a happy childhood because her stepmother loved her and treated her as if she were her own. She lived with her parents, older brother, and younger half-brother in Beijing’s Dongcheng District.

Wanrong was also fortunate because, unlike most fathers of his day, Rongyuan believed his daughter should be as well-educated as his sons. He sent Wanrong to the American missionary school in Tianjin. There, she learned English and to play the piano under the tutelage of Isabel Ingram, the daughter of American missionaries. Isabel was only four years older than Wanrong, and the two became great friends.

Not his first choice

During Wanrong’s childhood, China’s ruling class was in a precarious situation. Empress Dowager Cixi chose her future husband Puyi (also born in 1906) to be Xuantong Emperor when he was only two years old. Still, he was forced to abdicate in 1912 during the Xinhai Revolution.

Although he no longer had power over his people, officials of the Republic of China allowed Puyi and his court to retain their titles and continue to reside in the Forbidden City in the same style as they always had. This was allowed because many people, including the head of the republic President Yuan Shikai, expected the monarchy to be reinstated. In December of 1915, Yuan Shikai assumed the role of emperor. However, this move was so unpopular that he abdicated in March of 1916 and, being in ill health, died a few months later.

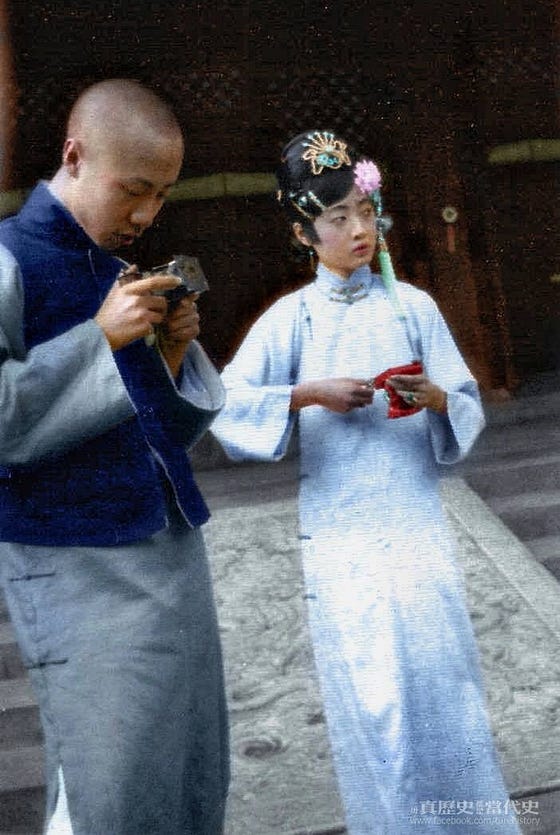

In 1922, when Puyi was 16 years old, the Dowager Consorts decided it was high time for him to marry. They showed him photographs of girls from families they deemed acceptable.

According to Puyi in his autobiography, the first photo that appealed to him was of Wenxiu. This caused a commotion among the Dowager Consorts because she wasn’t everyone’s favorite. One argued that Wenxiu wasn’t beautiful enough to be an empress.

Puyi agreed to marry the more comely Wanrong and retain Wenxiu as his concubine.

In the book The Last Emperor and His Five Wives, author Wang Qingxiang writes that Wanrong and Wenxiu had a strained relationship. Wenxiu moved into the palace first, and the pair exchanged less than cordial letters before Wanrong’s arrival.

As was the custom, Puyi married Wanrong and Wenxiu on the same night (in separate ceremonies), October 21, 1922. Unfortunately, the wedding night was a disaster for all concerned.

“I hardly thought about marriage and family. It was only when the Empress came into my field of vision with a crimson satin cloth embroidered with a dragon and a phoenix over her head that I felt at all curious about what she looked like.” — Puyi as reported by Edward Behr

Puyi had been attended primarily by eunuchs his entire life. He knew nothing about women, and sex was not something one discussed with the emperor. Various sources speculate that he may have been impotent, gay, bisexual, or so stunted emotionally by his unorthodox upbringing that sexual intimacy with women was beyond him. In his memoirs, he admitted that he enjoyed having his eunuchs beaten and had sadistic tendencies toward women.

In any case, when Puyi, Wanrong, and Wenxiu went to the Palace of Earthly Tranquility after the ceremonies were complete to consummate their marriages, Puyi panicked and fled the bridal chamber. His wives ended up sleeping in the Dragon Bed by themselves.

Life in the Forbidden City

Although their sex life was off to a rocky start, Puyi and Wanrong eventually came to get along well together.

In an interview with journalist Edward Behr, Wanrong’s younger brother Rong Qi said the couple enjoyed racing their bicycles through the Forbidden City, laughing as eunuchs scattered to avoid them. They also played tennis.

“There was a lot of laughter,” said Rong Qi, “She and Puyi seemed to get on well; they were like kids together.”

Less happy, perhaps, was Wenxiu. In his autobiography, Puyi admits that he rarely visited his consort. She lived alone in a spacious palace at the far end of the Forbidden City and slept a fair distance away from him.

“There was a generator in the palace, but it often broke down and it was common to have a power failure. Puyi didn’t live with his Empress or his Consort, so I had to live alone in the spacious Changchun Palace. The nights were so long and so horrible, and the loneliness in my heart was hard to be got rid of… Was this place really a palace of magnificence? Maybe it was just a macabre grave!” — Wenxiu as quoted in the book The Last Emperor and His Five Wives

By all published accounts, Wanrong wasn’t getting much affection from her husband either.

“The Emperor would come over to the nuptial apartments once every three months and spend the night there … He leave early in the morning on the following day and for the rest of that day he would invariably be in a very filthy temper indeed.” — Imperial Eunuch Sun Yaoting in a 1986 interview with journalist Edward Behr

One bright spot for Wanrong was that her former piano teacher Isabel Ingram, a graduate of Wellesley College in Massachusetts, came to live in the Forbidden City to serve as her tutor. Ingram and Puyi’s British tutor Reginald Johnston were the only people of “European stock” to attend the imperial wedding, according to travel writer Richard Halliburton in a letter to his parents. The writer visited Ingram while on a trip to China in 1922.

A Time magazine article dated May 12, 1924, revealed that Puyi and Wanrong adopted the Western names of “Henry” and “Elizabeth” and were fluent in English. They flouted tradition by taking tea outside the Forbidden City with Johnston.

In his 1925 book The Royal Road to Romance, Halliburton writes that the imperial couple learned “the speech, modes, and manners of the West” from their tutors and that Wanrong and Ingram sometimes dressed alike and traded clothes.

Expelled from the Forbidden City

While Puyi and his wives lived in splendor, a power struggle continued within the Chinese government. A coup staged by warlord Feng Yuxiang on October 23, 1924, put an end to their way of life. He changed the original agreement that had allowed the emperor to keep his title and declared that Puyi and Wanrong were now ordinary Chinese citizens. They were allowed three hours to gather their personal possessions and leave the Forbidden City for good. Feng expelled all the city’s residents as well.

Relocation to Tianjin

After leaving the Forbidden City, Puyi, Wanrong, and Wenxiu moved to a part of the Chinese city of Tianjin that was under Japanese control. They eventually resided in a house called the Garden of Serenity, but it was anything but. In his autobiography, Puyi states that this was when his two wives were in constant conflict. If he gave one a gift, the other demanded one equal or better. Eventually, Wenxiu got tired of the competition and the loneliness.

“Though we lived in the same building, we didn’t visit each other if there was nothing important. We seemed to be strangers with each other in the street. Wanrong put on airs of being an empress all day round and was arrogant. Puyi always believed what she said and they both showed the cold shoulder on me. The feelings between Puyi and me disappeared gradually day by day.” — Wenxiu as quoted in the book The Last Emperor and His Five Wives

Wenxiu conspired with some of her relatives to obtain a divorce and fled the compound in 1931.

After the divorce, Puyi stripped Wenxiu of her imperial titles. She taught school for a while and remarried. When she died in 1953, she was working for a cleaning company.

Before Wenxiu left, Wanrong tried to smooth things over with her, but by this time, Puyi wanted nothing to do with her. He didn’t spend much time with Wanrong either, so she was also lonely.

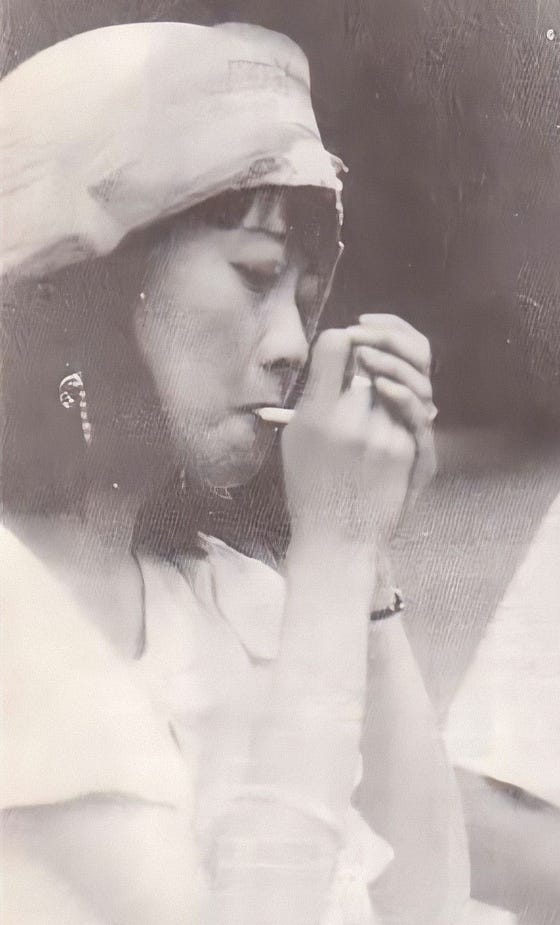

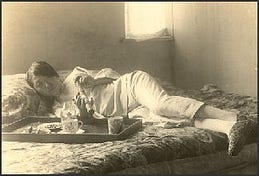

During their residence in Tianjin, some scholars assume that Wanrong became heavily addicted to opium, although she had been using it for some time. At first, Puyi encouraged this because she was easier to control when she was under the influence.

“Even If I had had only one wife she would not have found life with me interesting since my preoccupation was my restoration. Frankly, I did not know anything about love. In other marriages husband and wife were equal, but to me wife and consort were both the slaves and tools of their master.” — Puyi in his autobiography

Puppet rulers of Manchukuo

Puyi’s all-consuming passion was to regain his throne. When he and his wives left the Forbidden City, some of his advisors encouraged him to ally himself with the Japanese. Among them was his cousin Dongzhen (Eastern Jewel), raised in Japan and, in truth, a Japanese spy.

In the late fall of 1931, Dongzhen convinced Puyi to go to Manchuria, where the Japanese proposed to make him ruler of Manchukuo. Wanrong was opposed to this idea as she didn’t trust the Japanese.

She remained in Tianjin, but when it became clear that the Japanese would not let Puyi return, she joined him in Manchuria.

“The glorious advent of Manchukuo with the eyes of the world turned on it was an epochal event of far-reaching consequence in world history, marking the birth of a new era in government, racial relations, and other affairs of general interest. Never in the chronicles of the human race was any State born with such high ideals, and never has any State accomplished so much in such a brief space of its existence as Manchukuo” — Manchukuo press release, March 1, 1932

Shattered dreams

Desperately unhappy, Wanrong made two unsuccessful attempts to escape Manchukuo. Although she and her husband held the titles of Empress and Emperor, they were Japanese prisoners.

While Puyi was away addressing state matters, Wanrong engaged in at least one, possibly several, affairs with members of the imperial household.

The unabridged version of Puyi’s autobiography indicates that Wanrong gave birth to a baby boy that Puyi knew could not be his since he wasn’t having sex with her. (Other accounts say she had a girl.)

“After the child was born, he was thrown into the boiler immediately and dissolved, but she was told he had been adopted and remained dreaming of her son living in the world until her dying day.” — Puyi in the unabridged version of his autobiography (unsubstantiated)

Wanrong’s health began to deteriorate, and her addiction got worse. An article in the New York Times on November 21, 1934, referred to Wanrong as having a “nervous illness” and that she would be spending the winter in the port city of Dairen (now Dalian).

In April of 1937, a 16-year-old girl from a noble family named Tan Yuling joined the imperial household as Puyi’s concubine. Whether or not she had a sexual relationship with Puyi is unknown. By this time, he and Wanrong hadn’t shared so much as a meal in years.

Frequent visitors to the Salt Tax Palace were Puyi’s brother Pujie and his new wife, Lady Hiro Saga. Since Puyi had no children, he declared his brother as heir to the throne of Manchukuo. Puyi was forced to sign a document that if Pujie had a son, he would be sent to Japan to be raised. Wanrong’s hopes of being the mother of an emperor were dashed.

“Of course, I had heard rumours concerning such great men in our history, but I never knew such things existed in the living world. Now, however, I learnt that the Emperor had an unnatural love for a pageboy. He was referred to as “the male concubine”. Could these perverted habits, I wondered, have driven his wife to opium smoking?

— Lady Hiro Saga, Memoirs of a Wandering Princess

When Japan declared war on the United States and Britain in December of 1941, so did Puyi. Adolf Hitler officially recognized the state of Manchukuo. Wanrong’s family visited her there during the war and were dismayed by her condition. She was suffering from opium poisoning and had bouts of madness so extreme that she was sometimes chained up.

On August 9, 1945, the Soviets invaded Manchukuo. Puyi fled the palace with his brother and other officials leaving Wanrong, his concubine, and Lady Saga behind. The women attempted to escape to Korea but were captured by Chinese Communist guerillas in January of 1946. Puyi and his entourage attempted to take a plane to Japan, but were intercepted by the Soviets.

The women were imprisoned in various locations. Lady Hiro cared for Wanrong, who was suffering from opium withdrawal.

“All day long, the Empress rolled around on the wooden floor, screaming and moaning like a madwoman, her eyes were wide with agony. She could only feed herself, but she could no longer defecate by herself.” — Lady Hiro Saga, Memoirs of a Wandering Princess

Eventually, Wanrong became so ill that she was unable to walk. When Lady Saga and the other prisoners were moved to another location, she was left behind. She starved to death and died alone in her jail cell in Yanji on June 20, 1946. Her place of burial is unknown.

“ The experiences of Wanrong, who had been neglected for a long time, might be incomprehensible to a modern younger of New China. If her fate had not been arranged at her birth time, it would certainly be arranged at the beginning of the marriage with me. And then I often thought if she had divorced me in Tianijn as Wenxiu did she might have escaped it.” — Puyi in his autobiography